FTC warns users and providers of environmental certification seals.

Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sent warning letters to five providers of environmental certification seals and 32 businesses using those seals on their websites. The FTC is concerned that the seals may be deceptive according to Section 5 of the FTC Act, and may not comply with the agency’s environmental marketing guidelines, known as the “Green Guides.” The letters request that the recipients advise on what steps they are taking to bring their marketing into compliance. The agency is not disclosing the names of the companies that received the warning letters.

According to the Green Guides, unqualified general environmental benefit claims and environmental certificates or seals are likely to convey a wide range of meanings to consumers; i.e., consumers may see a picture of a leaf or the word “green” and assume that means the product is made of recycled materials or manufactured with renewable energy, even if those claims are nowhere to be found. Thus, the Guides caution marketers against using unqualified general environmental benefit claims – like “eco-friendly” – or environmental seals that do not convey “the basis for the certification.”

According to the warning letters, the environmental certification logos at issue do not convey the basis for the certification and are not accompanied by “clear and prominent qualifying language that limits the claim to a specific benefit.” Furthermore, the FTC cites their “.com Disclosures” guidance in noting that such a logo on a company’s website is “not likely an effective hyperlink label leading to the necessary disclosures.”

In its Business Blog, the FTC has a post on “Performing seals” which discusses the matter and advises on the following “key principles” about the use of environmental certifications and seals of approval:

- Without careful qualification, general environmental benefit claims pose a risk of deception. Under the FTC Act, deception can occur inadvertently if the marketer does not have substantiation for consumers’ interpretations of claims. For example, if a product conveys an unqualified “eco-friendly” claim, and a consumer interprets that to mean that the product is carbon neutral and non-toxic, then the product maker may be on the hook for deception unless it has evidence to prove that the product is, in fact, carbon neutral and non-toxic.

- Certifications and seals that don’t explain the reason for the thumbs-up may convey broad claims that can’t be substantiated. Bec

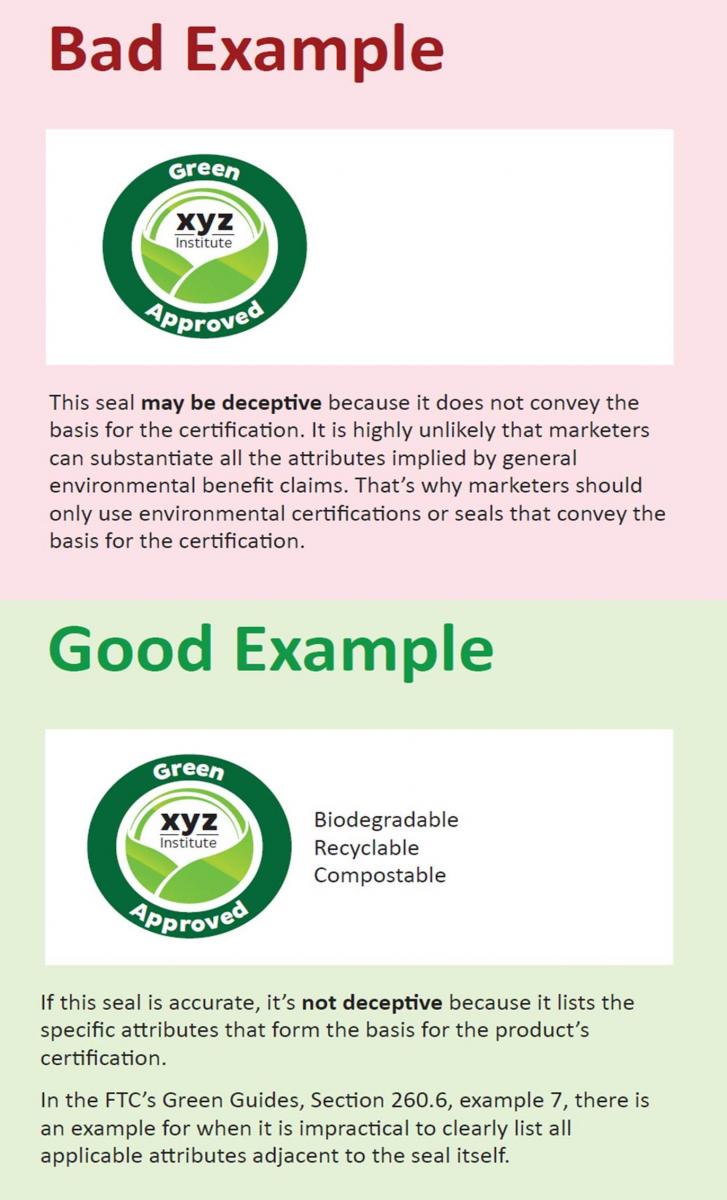

ause it is unlikely that companies can substantiate the vast array of claims that consumers can potentially interpret from an unqualified environmental certification seal, the FTC urges against using “seals that do not convey the basis for the certification.” The FTC’s blog post also includes a helpful visual illustrating good and bad examples of using an environmental certification seal (at right):

ause it is unlikely that companies can substantiate the vast array of claims that consumers can potentially interpret from an unqualified environmental certification seal, the FTC urges against using “seals that do not convey the basis for the certification.” The FTC’s blog post also includes a helpful visual illustrating good and bad examples of using an environmental certification seal (at right): - Companies can take steps to reduce the risk of deception. As discussed in the Green Guides, visuals like certification logos should be accompanied with “clear and prominent qualifying language that clearly conveys that the certification or seal refers only to specific and limited benefits.” In the “Good Example” of an environmental certification seal, for example, the words “Biodegradable,” “Recyclable,” and “Compostable,” are clearly displayed next to the certification logo.

- Logos themselves aren’t likely to be effective hyperlinks. Companies should not assume that readers will click on the logo image, and instead include explanatory information in large, easy-to-understand text, right next to the logo. In cases where not all attributes can be listed next to the seal, companies should display sufficient information upfront to explain why readers should click the clear and prominently placed link.

- Both the certifier and the advertiser have responsibilities under Section 5 of the FTC Act. In its letters to certifiers, the FTC notes that the certifiers’ websites do not appear to provide instructions to marketers on using qualifying language.

- The FTC has resources for companies that want to keep green claims clean. Here, the FTC refers to the Green Guides as well as its Statement of Basis and Purpose [PDF] for more detail. More resources are available on the FTC’s Environmental Marketing

The FTC has not determined whether the letter recipients’ claims violate the law and is not taking any law enforcement actions at this time.